Today’s proliferation of vacant properties is attributed to the 2008 housing bubble collapse, but property abandonment has plagued United States districts long before the predatory lending practices of the early aughts.

The story of New York’s South Bronx in the 1970s illustrates the ramifications of property blight on a community as well as the change that can be enacted when constituents and government unite to fight it.Stories like these inform the design of GovPilot’s Vacant Property Management solution.

Those who don’t remember history are doomed to repeat it. Join GovPilot for a glimpse into vacant property management’s shameful past, a peak at its much improved present and a preview of its promising near future.

The Bronx is Burning

Wrapped around glittering Manhattan like a mink stole, today’s South Bronx is a beacon of arts, entertainment and culinary delights, but it wasn’t always this way. The South Bronx of today is the result of years of residents and government leaders working together to pull the neighborhood out of a state of decline that reached its nadir in the 1970s.

Today's South Bronx is home to a variety of cultural and culinary attractions.

Today's South Bronx is home to a variety of cultural and culinary attractions.

A Google Images search of “the South Bronx in the 1970s” yields street photographs of children playing in rubble reminiscent of bombed European cities in the aftermath of World War II. The charred backdrop is the physical manifestation of improperly applied data, economic depression and the snowballing issue of property blight.

Many chronicles agree that the trouble started in 1963, with the completion of the Cross Bronx Expressway. The highway cut through the heart of the South Bronx,displacing thousands of residents from their homes. Droves of residents left the South Bronx for more suburban areas and property values plummeted. Remaining residents watched their living conditions begin to deteriorate. After all, post-WWII rent control policies provided building owners little incentive to maintain their properties.

The manipulation and misapplication of data catalyzed the South Bronx’s downward spiral throughout the following decade. In 1971, New York Mayor, John Lindsay, asked New York Fire Department chief, John O’Hagan, for a few million dollars in savings to help close a budget deficit. Chief O’Hagan turned to a team of statistical whiz kids from the New York City-RAND Institute to build computer models that replicated when, where and how often fires broke out in the city before predicting how quickly fire companies could respond to them. By showing which areas received faster and slower responses, RAND determined which companies could be closed with the least impact—or at least that was the intention.RAND’s flawed methodology and O’Hagan’s selective reading of its findings created a slew of problems for the South Bronx.

RAND’s study relied solely on response time rates. In addition to limiting itself to this one dataset, RAND’s sample was so small, unrepresentative and poorly compiled that the data indicated that traffic played no role in how quickly a fire company responded to a conflagration.RAND also incorrectly assumed that fire companies were always available to respond to fires from their firehouse — true enough on Staten Island, but a rarity in places like the Bronx, where every company in the entire borough could realistically be out fighting fires at the same time. In 1972, RAND recommended that the FDNY close 13 companies, oddly including some of the busiest in the South Bronx, and opening seven new ones, including units in suburban neighborhoods of Staten Island and the North Bronx.

The study’s flaws tended to make it appear that poor, fire-prone neighborhoods were actually over-served by the fire department. RAND’s recommendations to make cuts in these areas were heeded while the suggestion of closings in wealthier, more politically active communities went ignored by Chief O’Hagan.

“There was no question that where the Commissioner kept his car was not a house that was going to be closed,” says RAND’s Rae Archibald, who was later hired as an Assistant Fire Commissioner. “If the models came back saying one thing and [O’Hagan] didn’t like it, he would make you run it again and check, run it again and check.”

Retired Chief, Elmer Chapman, who ran the FDNY’s Bureau of Planning and Operations Research corroborates Archibald’s account of biased company closing. “Mostly we used [the RAND models] for the cuts, but if they came back saying to close a house in a certain neighborhood, well . . . if you try to close a firehouse down the block from where a judge lived, you couldn’t get away with it.” In those cases, continues Chapman, you could simply skip down the list of suggested closings to a company in a poorer neighborhood. Though RAND’s findings indicated that there were less painful cuts to be made, “the people in those [poorer] neighborhoods didn’t have a very big voice.”

As RAND’s assessment of firehouse use suggested,these economically depressed South Bronx neighborhoods were perhaps the nation’s most fire prone. Abandoned structures, which the South Bronx had in spades, are fire hazards. Decaying electrical systems go unaddressed, transients looking for shelter build makeshift fires for warmth and children and teens play with matches and fireworks on the premises.

Destruction caused by organic fires was compounded by damage resulting from intentional arson. South Bronx landlords unable to sell their property at any price and facing default on back property taxes and mortgages began to burn their buildings for the insurance money.

"Sometimes there'd be a note delivered telling you the place would burn that night," one man who lived through the period recalls. "Sometimes not. People got used to sleeping with their shoes on, so that they could escape if the building began to burn.”

With more conflagrations and less firehouses, fire-related fatalities doubled. Between 1970 and 1980, seven census tracts in the Bronx lost more than 97 percent of their buildings to fire and abandonment. Forty-four tracts lost more than half. Further devastation led to further population decline. During this decade-long period, 57 percent of South Bronx residents fled the area.

Phoenix

Americans alive during this era remember two major events that marked a turning point for the South Bronx. The first is a false memory that rightfully drew national attention to the plight of the South Bronx and the second signaled the beginning of the area’s renaissance.

Viewers who watched the Los Angeles Dodgers face off against the New York Yankees during Game 2 of the 1977 World Series may have forgotten the loss of the home team, but they surely remember witnessing a piece of broadcasting history. A few hours prior to the first pitch, a large fire had broken out in an abandoned school near the South Bronx’s Yankee Stadium.The fire was still burning without a fire truck in sight when the camera took a break from broadcasting the action on the field to pan over the area surrounding Yankee Stadium. Sportscaster, Howard Cosell, uttered,“There it is, ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning.”Though Cosell did not actually phrase it with such eloquence, his summation of the sight caught national attention and served as the impetus for a visit that changed the course of South Bronx history.

On October 5, 1977, President Jimmy Carter’s limousine made a surprise stop on Charlotte Street in the South Bronx. A pile of rubble more than it was a city block, Charlotte Street epitomized the squalid conditions that soiled daily life for many South Bronx residents.

Photographs show President Carter shaking hands with locals, stumbling over debris and staring with disappointment at a once lively district that had literally fallen to pieces. So began what officials have called the nation’s largest rebuilding effort.

Carter passed legislation that delays insurance payments for suspicious blazes.Local government leaders partnered with community, volunteer and religious groups to set about rebuilding, reclaiming and revitalizing major portions of the South Bronx. Decades of teamwork have culminated in the South Bronx of today, a district that offers restaurants, shopping centers and walking tours of historic sites.

Legacy

GovPilot has taken two important lessons from this story of decline and revival.The first half of the story—the disregard for data at the expense of resident safety, the vicious cycle of economic depression and property abandonment—is cautionary. The second half—the part that illustrates the great change that can come about when government and constituents work side by side to solve an issue—is inspirational.

Both lessons have informed the design of GovPilot’s Vacant Property Management solution. Digital forms grant residents a voice and automated workflows ensure that they are heard by government. Information aggregated from forms is stored in a comprehensive database accessible to all government departments and can be analyzed and publicized via a geographic information system (GIS) map for optimal trend recognition and transparency.

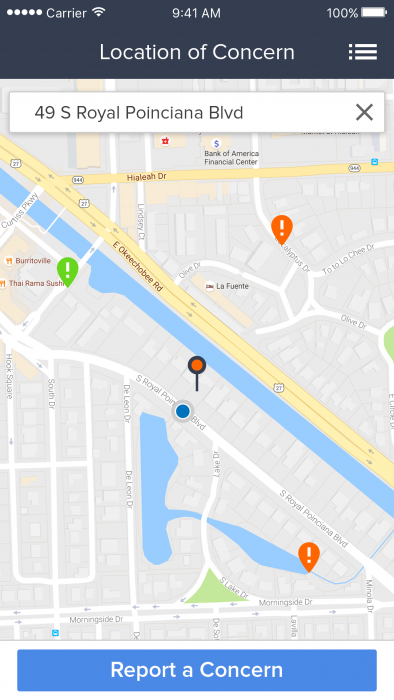

GovPilot is looking forward to further improving relations between government and constituents as they fight the nation’s current outbreak of vacant properties. Coming soon to Android and iOS, GovPilot’s GovAlert mobile app empowers constituents to inform government officials of blight-related issues with unprecedented immediacy and convenience.

Users can snap a picture of a blight-related problem on their smartphone and supplement the image with descriptive text.In a tap or two, the concern is sent to their local government, as determined by device location settings.The appropriate government official receives the alert in real time.

The GovAlert mobile app will soon be available for Android and iOS.

The GovAlert mobile app will soon be available for Android and iOS.

If the administration is already a GovPilot client, the concern is addressed through the same efficient GovPilot process that powers successful vacant property management programs in cities, like Newark, New Jersey. Even if the administration does not use GovPilot, officials are still notified.

In GovAlert, government and constituents have a tool sophisticated enough to fight property blight in the 21st century. Keep reading GovPilot’s blog for details surrounding the app’s release and updates on the ongoing war on vacant properties.

Schedule a demo to learn more about GovPilot.